It should be noted that the modern conception of Indonesia rose out of an era of colonialism and struggle against the military oppression of both Western colonial powers and Japanese imperialism. In 2008, The New York Times regarded President Suharto’s rule of Indonesia as ‘one of the most brutal and corrupt of the 20th century’.

According to Transparency International, it is estimated that Suharto embezzled between fifteen to thirty-five billion US dollars during the length of his presidency, with the exact cost of human life still unknown. This was largely the result of Suharto’s authoritarian ‘New Order’ that saw corruption and the militarised suppression of political opposition as a way of life.

Despite these atrocities, Suharto’s anti-communist sentiment won him a favour from the US, who brought international support and legitimacy throughout the Cold War, until the collapse of the thirty-year rule, regarded as successful, primarily for its ability to maintain order and control across the archipelago.

Following Suharto’s resignation in 1998, Indonesia went through periods of increasing democratisation. Since then, Indonesia has begun its long recovery from the 1997 Asian financial crisis, East Timor received its independence, and major restructuring has been undertaken in areas of public life under the current president, Joko Widodo.

Like other parts of Asia, tension has resurfaced from the sudden modernisation of the country, with government encroachment on traditional ways of living, particularly for the poorest and most vulnerable parts of Indonesia. Currently, homes in Tamansari, Bandung, are being demolished by the government, much to the disdain and bewilderment of citizens like terorski, who uses an alias for fear of repercussion.

Like countless activists before him, terorski is a visual artist whose work has become an important tool of resistance against the growing authoritarianism of Joko Widodo’s plans for what teroriski sees as the increasingly undemocratic outlook for the economic reformation of the country. For him, modernisation is coming at the expense of people’s homes and livelihoods, with plans for further mechanisation targeting the most vulnerable citizens with police violence and forced eviction – usually for the benefit of the wealthiest few.

According to terorski, there has been serious effort to implement restrictions against free speech with the government attempting to implement ‘RUU Pertanahan’, a bill that holds back a citizen’s right to freely protest against forced evictions.

According to terorski, “Under RUU Pertanahan, you will be jailed by the government for fifteen years if you resist eviction.”

Laws like ‘RUU Pertanahan’ are often used to justify acts of police brutality, similarly to how anti-terror laws in the West have allowed enforcers to surveil, subjugate and attack lawful dissidence. It plays into the idealised myth that governments use laws to restrict people’s freedoms for the utilitarian benefit of everyone at large.

Terorski shows me a short video of a suburb being demolished in the area of Tamansari. Here, a yellow excavator demolishes somebody’s home. Those frequently harmed by these violent tactics are the unemployed, women, and children.

“This video is only a small part of the thousands of forced evictions carried out by the regime in various regions throughout Indonesia”, terorski continues, “My artwork is never enough to represent any misery experienced by the affected citizens.”

Ultimately, terorski’s story raises more international concerns that economic and technological progress comes to people at the cost of their liberty and wellbeing. Moreover, the implementation of these progressive reforms allows governments to act with levels of authoritarian disregard towards their citizens.

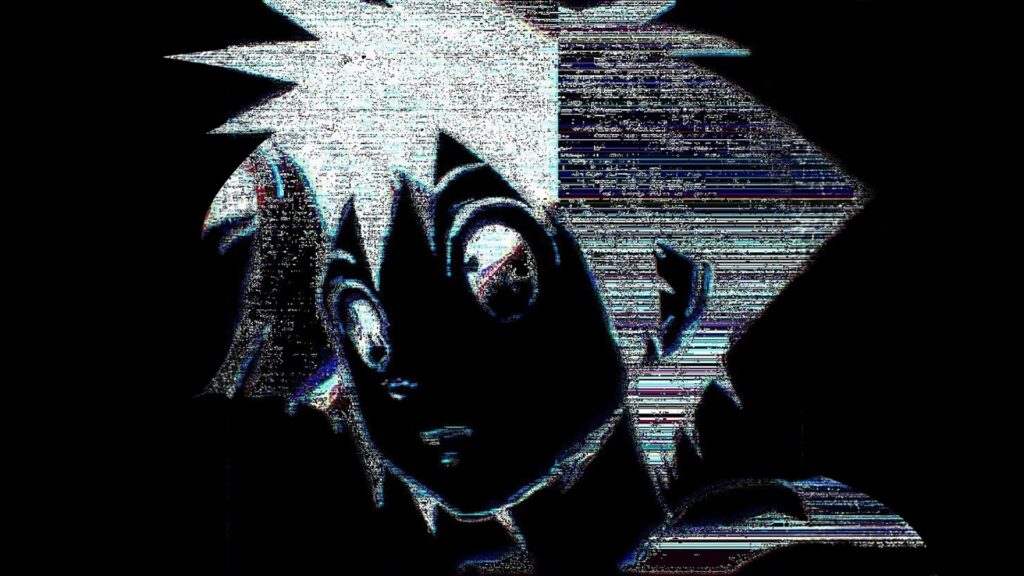

This authoritarianism brought terorski to an art form where concepts show life inside, what he calls, “A Dystopian Society”, where life is about hiding your real identity for fear of repercussion. Whether it’s Hong Kong or Tamansari, it seems to conceal your true identity lies at the heart of revolutionary activism.

I asked terorski to describe one of his illustrations.

“This poster was created to encourage everyone to protest the cancellation of the RUU Pertanahan law.” He continues: “There are two figures in this illustration, the full face is the authoritarian president Suharto of his day, while the second face is the current Indonesian president, Joko Widodo (colloquially known as Jokowi). I want to campaign that there is no difference between the current regime and the previous regime, it’s time to take to the streets. That’s the reason I added the text ‘tunggu apa lagi? Ayo turun ke jalan.’ Which means, ‘What are you waiting for? Let’s join the protest.”

Stay in touch with

Instagram

Cover photo: Terorski at the RKUHP, RUU Pertanahan Law protest – September 2019

Next story